By Amanda Lopatin, HJHA Intern

By Amanda Lopatin, HJHA Intern

When I asked Sherry Merfish to tell me her title, she wasn’t sure what to say, and after talking with her for an hour, I understand why. Sherry is a Jewish woman from San Antonio, a mother, an attorney, and a feminist. Sherry told me that the title that best encompasses all of her roles is “activist,” and I agree.

Last month, I sat down with Sherry to interview her about her archives, which Sherry generously donated to Rice University and the HJHA. Beginning in the 1980s, Sherry led a nationwide campaign against the term “JAP,” or “Jewish American Princess.” A few months ago, Sherry donated her files from this campaign to the Archive.

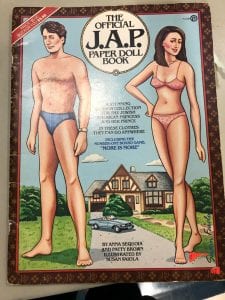

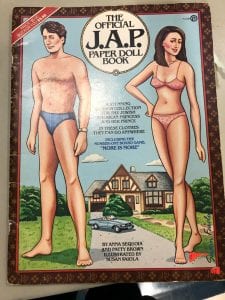

Though Sherry had heard the term “JAP” in passing during her childhood, she only began to realize its abhorrent sexism and anti-Semitism after becoming a mother when she saw The Official JAP Handbook for the first time. Sherry found The Official JAP Handbook at Houston’s Jewish Community Center book fair in the 1980s, and she became increasingly appalled as she perused it. Sherry realized that age-old Jewish stereotypes (such as materialism, parasitism, and lack of trustworthiness) were being attributed to Jewish women. Sherry knew immediately that she needed to do something.

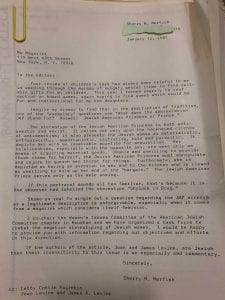

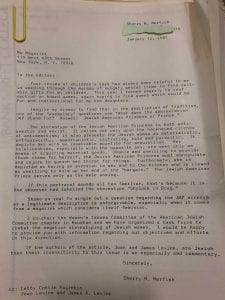

To raise awareness, Sherry started by bringing the issue to the Women’s Issues Committee of the Houston Chapter of the American Jewish Committee (AJC). But Sherry didn’t just want to talk about how despicable the stereotype was. She wanted to take action to eradicate it altogether.

Sherry Merfish and Ellen Cohen (currently a member of the Houston City Council, and at that time the Executive Director of the American Jewish Committee) went to a meeting of the Houston Rabbinical Association (HRA) with a goal: to get a resolution passed addressing the stereotype. The association, which was made up of all men at the time, blew off Sherry and Ellen’s concerns, telling them to learn to take a joke. Sherry quickly realized that she would not win the Rabbis over by telling them how hurtful the sexism of the stereotype was. Instead, she focused on this term being “anti-Semitism in new packaging.”

Within an hour, the Houston Rabbinical Association accepted a resolution to address the negative stereotyping of Jewish women, to educate young people about the harms of the stereotype in religious and day schools, and remove all merchandise touting the stereotype from their gift shops.

Sherry’s success with the HRA received national attention, and the AJC held a national press conference in New York where they invited Sherry to speak and share her work. This press conference sparked a national movement to fight against the JAP stereotype. Sherry fought the “JAP” stereotype everywhere she found it — on greeting cards, in synagogue gift shops, on college campuses, and even on Saturday Night Live.

Sherry’s success with the HRA received national attention, and the AJC held a national press conference in New York where they invited Sherry to speak and share her work. This press conference sparked a national movement to fight against the JAP stereotype. Sherry fought the “JAP” stereotype everywhere she found it — on greeting cards, in synagogue gift shops, on college campuses, and even on Saturday Night Live.

Years of leading the campaign against the JAP stereotype made it clear to Sherry that she wasn’t content practicing law, but that she wanted to continue to change the world in bigger and bigger ways. Sherry decided to work for EMILY’s List, where she led a 20 year long career of activism in electing democratic women.

Thanks to Sherry’s work, the JAP stereotype largely disappeared from popular culture. It does, however, pop up now and again in television shows or books, and when it does, Sherry is still called on to speak out against it.

The Sherry Merfish Papers (MS-815) include letters, speeches, and JAP paraphernalia, and they are available to the public for viewing and research in the Woodson Research Center in Fondren Library.

Correction: A previous version of this blog post inaccurately stated that Sherry’s work to fight the JAP stereotype took place the the 1970s.

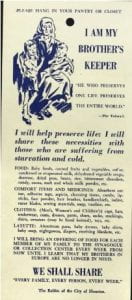

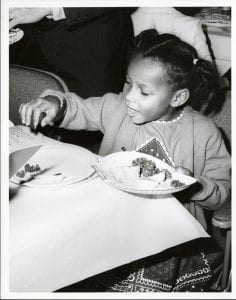

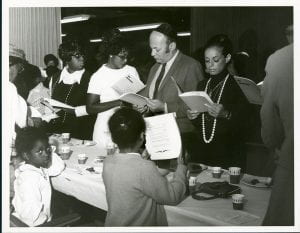

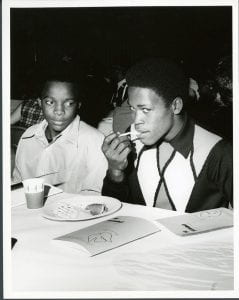

It seems that the interracial Seder was one of the first genuine interactions between Houston’s black commu

It seems that the interracial Seder was one of the first genuine interactions between Houston’s black commu