Passover is a holiday about acknowledgment of the other and subsequent redemption. During Passover we recite this passuk: “A wandering Aramean was my father [’arami ’oved avi]; he went down into Egypt and lived there as an alien, few in number, and there he became a great nation, mighty and populous” (Deuteronomy 26:5). These words serve as a reminder that the Jewish people’s concern for others should stem from the historical experience of their own people.

The Seder is a time not only to reflect on the story of the Jewish people as oppressed and redeemed, but also to acknowledge the inequities that still exist. The very fact that we read in the Haggadah that we are still enslaved is perhaps the most instructive of this concept, “Whoever is hungry, let him come and eat; whoever is in need, let him come and conduct the Seder of Passover. This year [we are] here; next year in the land of Israel. This year [we are] slaves; next year [we will be] free people”. These words have inspired people from all faiths in their quest for freedom.

During the Civil Rights Movement, the Seder acted as a bridge between white Jewish Americans and black Americans. This is the principle that underlies the Freedom Seder and Congregation Beth Yeshurun’s Interracial Seder as well as the shift from the Seder as a Jewish tradition to a meal of contemporary intersectionality.

On April 4, 1969, the one year anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, the first Freedom Seder was held in the basement of an all-black church in Washington DC. Attendees used Rabbi Waskow’s Freedom Haggadah, which incorporated both historical Jewish elements and discussion of social-justice heroes such as Gandhi and MLK. It was this Seder, with 800 Jews and non-Jews, white and black, that allowed for the Passover Seder to be viewed as a Jewish avenue for social justice.

On April 4, 1969, the one year anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, the first Freedom Seder was held in the basement of an all-black church in Washington DC. Attendees used Rabbi Waskow’s Freedom Haggadah, which incorporated both historical Jewish elements and discussion of social-justice heroes such as Gandhi and MLK. It was this Seder, with 800 Jews and non-Jews, white and black, that allowed for the Passover Seder to be viewed as a Jewish avenue for social justice.

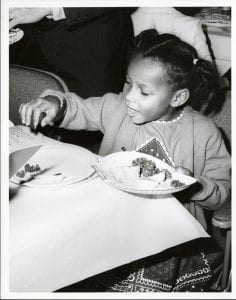

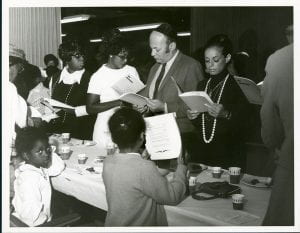

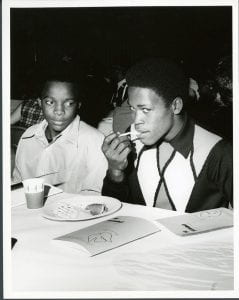

As I was processing a box of photographs from the Congregation Beth Yeshurun collection, I came across an envelope full of photographs entitled “Interfaith Seder.” These photographs, in pristine quality, were not just reflective of an Interfaith Seder. Rather, these photographs depict a racially integrated and community-oriented Seder of individuals from different faith backgrounds. On April 4, 1971, on the third anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s death, Beth Yeshurun and the Julia C. Hester House conducted their own interracial Seder.

The Julia C. Hester House is an organization that works “to enhance the quality of lives in the Fifth Ward and the surrounding community through programs and services promoting self-empowerment”. Congregation Beth Yeshurun’s Message Announcement for the event stated, “V. Besselle Atwell, dynamic director of the bustling neighborhood center … is a firm believer in the maxim that mental and spiritual ghettos are even more binding than physical ones.” Reading this statement, I was instantly reminded of a topic discussed at my own Seder this year, the Slave Bible. The Slave Bible was the bible used by Christian Missionaries to convert slaves in the Caribbean. Within this Bible, it was discovered that the entire Exodus Story had been removed, so as to avoid inspiring the slaves to commit acts of rebellion against their masters. It is striking to think about how the Passover Story was viewed as a threat to the entire construction of slavery, as something that could free one not only from their own ‘mental or spiritual ghetto,’ but from the chains of physical slavery as well.

It seems that the interracial Seder was one of the first genuine interactions between Houston’s black community and the Houston Jewish Community as cited in Congregation Beth Yeshurun’s ‘The Message,’ which noted that “[s]ince real contact with Houston Jews has, unfortunately, been quite minimal, it was felt that no interracial experience could be more valuable than participating in the Seder ceremony.” From Waskow to Congregation Beth Yeshurun, the Seder was used to break the social and political barriers of segregation and create ties between the black American community and white Jewish American communities.

It seems that the interracial Seder was one of the first genuine interactions between Houston’s black community and the Houston Jewish Community as cited in Congregation Beth Yeshurun’s ‘The Message,’ which noted that “[s]ince real contact with Houston Jews has, unfortunately, been quite minimal, it was felt that no interracial experience could be more valuable than participating in the Seder ceremony.” From Waskow to Congregation Beth Yeshurun, the Seder was used to break the social and political barriers of segregation and create ties between the black American community and white Jewish American communities.